Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions

Portraits 360 Sek (2002)

PHOTOGRAPHY / CREDITS / PRESS

I was born and my nose was a catastrophe.

At the age of one I was cross-eyed.

At two I was still cross-eyed, and wobbled about on bandy legs, constantly bumping into something or another.

At three I was covered in bruises and had a black tooth.

At four I stopped speaking, and would only sing shanties and hymns.

At five I cut off my clitoris and burnt my left hand in the ironing machine.

At six I was still bald-headed.

When I was seven my mother realized there was a problem with my ears.

When I was eight I thought having stick-out ears meant you could fly, so I flew into the radiator and lost my black tooth.

At nine I got cellulite.

At ten I wound adhesive tape round my head and then tried to staple my ears flat against my skull.

When I was eleven my mother and I stood next to each other and she knew that one day I would look exactly like her.

When I was twelve my mother knew that I would grow up to be 2.13 metres tall and started pumping me full of hormones.

At thirteen I was guzzling hormones and my voice began to break.

At fourteen I was guzzling hormones and still had no hair – under my arms.

At fifteen I was a hormone. And although I knew I would never have breasts at last somebody turned up who looked for my clitoris.

At sixteen I sat next to my grandmother and mother and I suddenly realized that for me things were going to be a lot worse than my mother would ever be able to admit.

...

I am 28. I am married. And my husband calls me monster.

(Wiebke Puls)

CREDITS

Directed by Michael Laub

Set Design Jean Baptiste Trystram / Michael Laub

Costumes coordinator Katie Lloyd

Light Annette ter Meulen

Video Alexander Grasseck / Marcel Didolff

Dramatic adviser Imanuel Schipper

Technical Coordinator Julian Richter

Text-machine operator Helge Schiller

Assistant Director Jörg Karrenbauer

Production assistant Claudine Profitlich

Trainee (stage direction) Björn Adelmeier

Trainee ( video sequences) Maik Reif

Trainee ( dramatic composition )Katja Starke

Remote Control Productions Management Bertie Ambach

with Mira Bartuschek, Heide Grübl, Wiebke Puls, Maja Schöne, Ursula Semmelhack, Matthias Breitenbach, Ben Daniel Jöhnk, Frank Kienitz, Wolfgang Kremer, Bern Moss, Albert Niehörster, Samuel Weiss.

and Evelyn Groschopfer, Julia Hilbert, Gabriele Weist, André Dahms, Peter Janson, Mark Brautschitsch.

Produced and commissioned by Deutsches Schauspielhaus in Hamburg

PRESS

K. Müller-Roselius. Die Welt, 29.4. 2002

Just try to describe yourself in six minutes flat. Six minutes are 360 seconds and correspond approximately to the duration of a pop song. In the modern world, nobody has more time for a flirt at the bar or a job interview. And so Belgian director Michael Laub invited twelve employees -- from lead actor to cleaner -- of the Schauspielhaus in Hamburg to talk about themselves in the scope of a six-minute stage appearance. The premiere was on Saturday. A digital stopwatch in the top left corner of the stage timed precisely 4,320 seconds, and then the evening was over. In the meantime, the twelve 360-second portraits had imperceptibly merged into one big picture: a portrait of the Schauspielhaus itself.

Frauke Hartmann, Frankfurter Rundschau, 30.4. 2002

Like any other evening at the Schauspielhaus, the audience is greeted by Albert Niehörster, the front-of-house chief, wearing his uniform. Only this time he is standing on the Malersaal stage, empty save for a digital time display. He is followed by Wolfgang Kremer, Stromberg's chauffeur, who recalls a portentous conversation about music he once conducted with Laub. No, he told the director, the sound of Mahler didn't make him weep, but that of Sibelius almost invariably. Promptly, the music starts up, and Kremer, not a professional actor, manages to stay on his chair for all of four minutes and endure the audience watching him listening, breathing and gulping back tears. These portraits draw their strength from the friction between such genuine moments bordering on the embarrassing and the stage reality which is produced yet authentic. Whereby Laub appears as the initiator of the self-revelation and secret master of genre mixing.

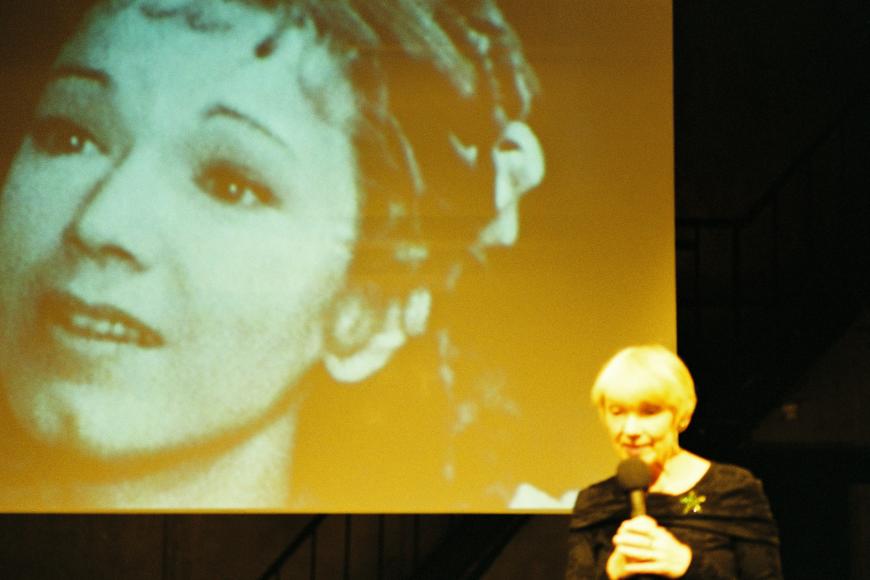

Laub, who has been working with amateurs for some time now, also fetches onto the stage, along with their favourite songs and passages of text, the extremely tall Frank Kienitz, a stage extra, and the cleaning woman Ursula Semmelhack,. It is a risky venture; one that in equal measure deploys cliché and the contrast to the artistic. Heide Grübl, tour-guide-like, relates the history of the Schauspielhaus and its directors. Huge, blown-up photos are flashed onto the set: Heide Grübl as a young actress working under Fassbinder and Zadek. As if wanting to prove her credentials, she performs, screams into a telephone, deeply injured, and abruptly switches back to the vivacious but unmoved narrative tone she began with. Laub, she tells us, sent her looking for costumes, but none of her early costumes was still in the repository.

A major highlight is Laub's handling of video, for instance when he counteracts the romantic side of the young actress Mira Bartuschek. Or when he presents as a home move the lonely insomnia of the actor Matthias Breitenbach. These essays are all intimate trifles, yet they touch on fundamentals by creating distance. With the aid of Ben Daniel Jöhnk, Laub attempts to reconstruct a Baroque Flemish painting. Between a dead pheasant and a bowl of grapes, the bare-chested actor lies on a table, eating grapes, drinking red wine, and placing on his face edible snails that he moistens with a spray device. There is a reference to Peter Greenaway there, too. But the sharp edge of this scene comes above all from the insertion of a videotape in which Jöhnk tramples and crushes a snail in a fit of rage brought on by the sheer impossibility of the acting task we are witnessing.

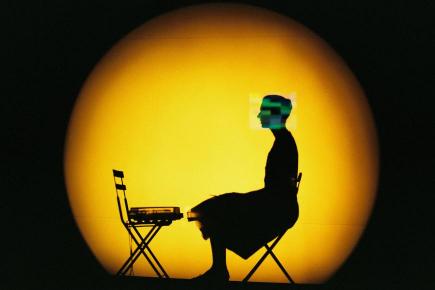

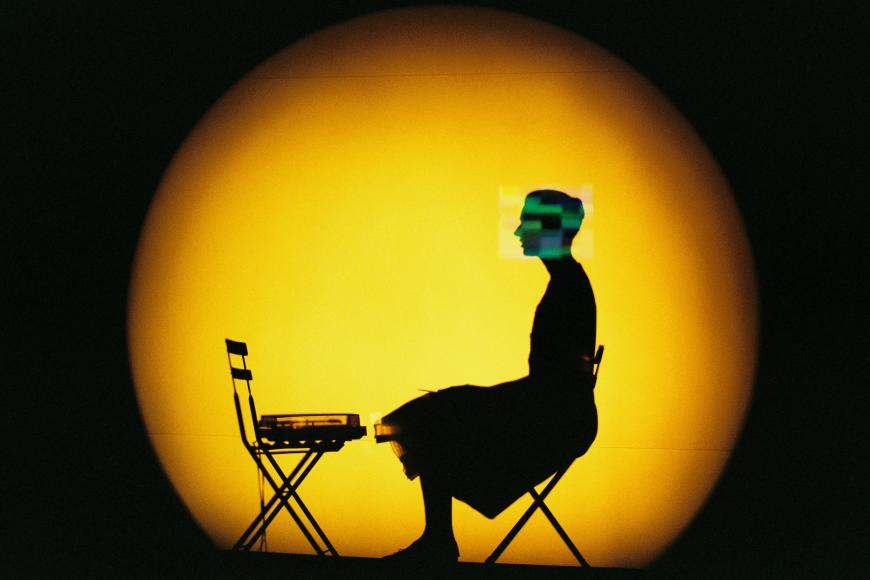

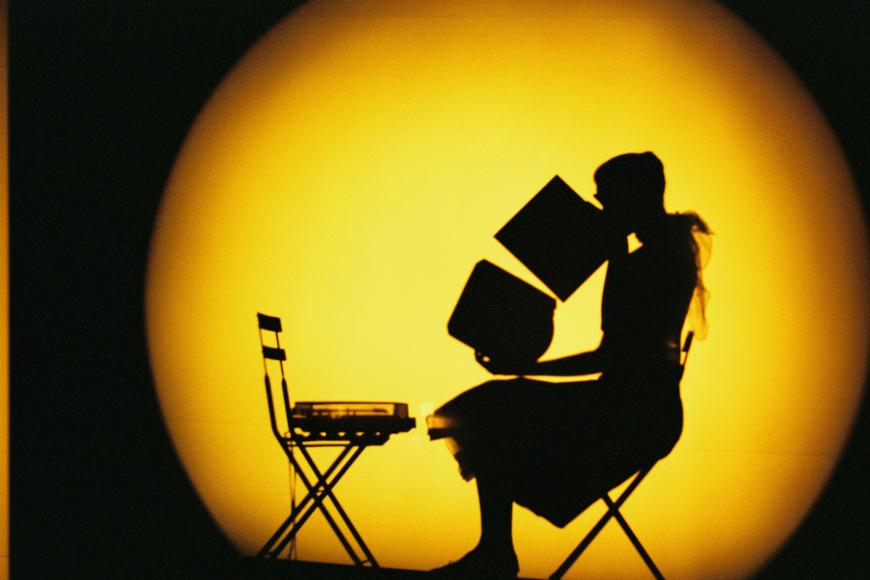

Irritatingly tragi-comic are likewise the revelations, conveyed purely by acting, of Bernd Moss, Maja Schöne and Samuel Weiss. The latter characterizes himself solely on the basis of quotes from reviews. The electronically distorted voice of Wiebe Puls, a silhouette seated behind a paravent, gives an account of the brutal coming of age of a girl who suffers from being different. And then she starts to sing, softly. This is where Laub most impressively succeeds in fracturing the image and sound of Puls' mechanically delivered Shock-Headed Peter text, and in doing so place something truthful in the minds of the audiences. What comes about is poetry, and what more does one want?

Helmut Schödel, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 30.4. 2002

Frank Castorf is a great director. He tells it like it is, for one thing, is hardly the Mr. Clean of the theatre. And that's the problem: has even one of his admirers ever bothered to think about how much dirt the art of Castorf makes? For instance, his outstanding production of Elfriede Jelinek's "Raststätte" -- that play with the frequent visits to the toilet? "That didn't half look bad," says Frau Semmelhack, the cleaner at the Deutsches Schauspielhaus in Hamburg. They placated her with the words, ”Uschi, the brown stuff is just healing earth." That's what remains of deconstructivism: revolting gobs.

Frau Semmelhack was newly divorced and glad to get a job in the theatre. And then Castorf came. Followed by "Clockwork Orange" -- "hard to clean up after," recalls the little woman with a bucket equipped with a mechanism for wringing out cloths. Even Max Frisch's "Biedermann und die Brandstifter" was a challenge. But now she's happily remarried, and obliviously dances across the stage with here broom and rag, listening to her favourite hit "When you lost your lover, there's a feeling to discover".

Her appearance is the finale in a wonderful evening of theatre directed by Michael Laub. Tom Stromberg, the director of the Schauspielhaus, had invited Laub to portray his actors and staff. No portrait was allowed to exceed six minutes. The resultant twelve portraits add up to Porträts. 360 sek.

Evelyn Finger, Die Zeit, 8.5. 2002

By linking the unstructured with the well-calculated, the director subtly conveys to the audience some idea of those elements of which theatre is composed: exuberance and effort, yearning and application, happiness and fear. Yet because the individual portraits are so direct, as an exercise in vanity this self-portraiture remains modest. The quietly non-intentional gets the same six short minutes as the noisily exhibitionist, and that is why, in the final resort, the theatre emerges victorious as a powerhouse of the imagination as opposed to a factory of personalities.