Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions

Snapping 2025 / Snap Dance

PHOTOGRAPHY / VIDEO / CREDITS / PRESS

"Snapping 2025 / Snap Dance" is the latest multi-screen video installation by Michael Laub. Produced in Cambodia, it revisits his 1981 installation "Snapping", originally created in Belgium, Sweden and Thailand, of which only a faded trailer remains, while expanding the concept through dance. Portraying a diverse cast of individuals and dancers ranging from ballet and Apsara to hip-hop, the work unfolds with the sound of footsteps, breath, rustling costumes, and snapping resonating through the space.

CREDITS

Snapping 2025 / Snap Dance

video installation

Produced by The French Institute of Cambodia in co-production with Phare Ponleu Selpak and Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions

Conceived and Directed by Michael Laub

With:

Snapping 2025: Anna Aleeva, Hak Chan, Ruon Dit, Vankosal Keo, Annalise Khen, Vanthy Khen, Dara Korn, Mathieu Ly, Rapech Loek, Chandy Mo, Coralie Morillon,Keokanitha Phalla, Clément Perocheau, Loeurt Phorn, Natalie Rasmey Devi Onezime, Reaksmey Yean, Em Riem, Khorn Soun, Chantrea Tob, Thina Tola, Sreythy Touch, Srey Pov Yoeun, Samnang Yorn

Snap Dance: Marloon Aranjuez, Océane Decroze, Svetlana Epifanova, Annalise Khen, Chomrern Khoun, Rae Price, Sambath Sat, Solida Sang, Nina Sek, Sokim Seng, Kim an Thorng, Sothydacharline Vanthan.

Solos: Annalise Khen, Rossika Khen, Rae Price, Sokim Seng, Svetlana Epifanova

Videos: Oyen Rodriguez

Sound: Chandy Mo and Chen Phy

Choreography adviser: Vanthy Khen

Executive Production: Coralie Morillon

PRESS

Shaun Duff, independent journalist, published in the Phnom Penh Post, 7 November 2025

Snapping back: Michael Laub and fifty years of controlled chaos

Michael Laub is somewhere between Brussels and Cambodia when we connect via video call and the first thing he wants you to know is that he's not a European theatre academic. Nor is he another art-house darling mining Southeast Asia for exotic material. Not even, despite four decades of critical acclaim and retrospectives, particularly interested in being taken seriously.

“People often confuse me for an academic,” he says, “but basically, I have a punk sensibility.”

It's a telling opening from the 72-year-old Belgian director and choreographer, whose work has been labelled “post-dramatic theatre” for decades by critics and scholars. He's preparing for the Phnom Penh premiere of Portrait Series – Snapping 2025 / Snap Dance at the French Institute of Cambodia (IFC) this week, following its debut at an urban festival in Battambang on November 3.

The multi-screen video installation represents both a homecoming and a reinvention, a return to work he created in 1981, now reimagined through Cambodian dancers and contemporary lifestyles.

Against obsolescence

In 1981, Laub was emerging from Maniac Productions into what would become Remote Control Productions, right in the immediate aftermath of the post-punk, performance-art moment. The flower power kids had gotten haircuts. Reagan was about to take office. MTV was months away from launch.

“In terms of performance, it was a reaction to a form – theatre – that I considered obsolete, as opposed to other art forms at the time that were a lot more relevant – pop art, independent cinema and punk rock, which was a major influence on me,” he explains. “The conventionalism of theatre – and I make a clear distinction between conventionalism and classicism; I have the deepest respect for classicism – but theatre seemed particularly contrived, and in a way hypocritical, because it lacked spontaneity. I was reacting against that because it irritated me, and against myself and my own limitations.”

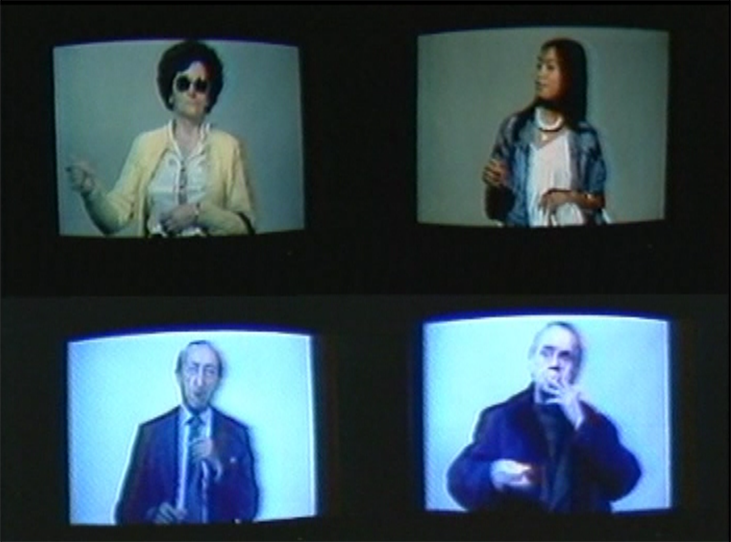

The original Snapping, created when Laub was in his late twenties, stripped theatre down to its essentials: people from all walks of life were portrayed, guided only by rhythm, breath and the snap of fingers. No elaborate sets. No narrative arc. No theatrical artifice.

“That's why it was Maniac Productions, obsessive,” Laub says. “The repetition connected to minimal music at the time, like Steve Reich, but also to obsessive, neurotic patterns that were dysfunctional as opposed to the idealistic flower power period that preceded punk. My relationship to theatre at the time was practically post-mortem. I thought the thing was dead.”

When German professor Hans-Thies Lehmann later coined the term “post-dramatic theatre” to describe work like Laub's, the director found himself repeatedly categorised.

“I've been called 'post' a lot of things and now my main concern is not to be 'post-life',” he says with the flat humour of someone who's been post-everything except alive.

Remote Control

The company name that would define his career emerged from what Laub calls his “masochistic period in Sweden”. He had good contacts with museums and institutions, but no real audience. He became, he says, “frankly bored out of my mind”. Then cable television emerged, multiplying channels from three to dozens overnight.

“I was very into William Burroughs and the cut-up technique,” Laub explains. “Switching channels corresponded to that cut-up method. You could make a narration out of it. That's where the 'remote control' concept came from.” We bond over Burroughs for a minute – Laub lights up talking about The Wild Boys, which he reread recently. “He was a visionary,” he says. “The guy was a genius.”

Another crucial influence was Miles Davis.

“Miles Davis defined cool – timeless cool. A great improviser who got away with it because he relied on a tight rhythmic structure that he could always fall back on. The first time I listened to it I thought, wow, that rhythmical section is really bulletproof; it's so cool. And then he's able to go all over the place because he's always able to lean back into that. And I thought, this is something that I could apply to a completely different form.”

This became Laub's method: Burroughs' cut-up technique, Davis' structured improvisation, minimal music's repetition.

It’s clear he enjoys this mash-up of form and people. Different people from different places in Snapping, and dance and video – form – in Snap Dance.

“I use devices from other media and adapt them. When I'm commissioned to do a piece, for example at the Burgtheater – I only accept if I can mix the big stars with the guy who runs the canteen. My work is rhythmical. On stage, all you get is sound, image and rhythm. It can be slow, but it must have rhythm.”

“Even if I have a framework, a lot of the material is created during the rehearsals. which keeps it alive. There's enormous input from my performers. I always tell them, 'you can try anything you want' – until about two weeks before we open the show,” he says in all seriousness. “Then, unless you come up with something else really genius, I'm going to take strict editorial control over the whole thing in order to get the right rhythm.”

“I audition obsessively to find people who will bring me the kind of material I want. So it's really collaborative until the point I have that material – it gives me the illusion of control.”

It's a system that allows for what seems like contradictions – the exhaustive rehearsal of his choreographies, contrasted with pieces like Snapping which are “based on the here and now”.

“On that score, it’s a temporary return to some of my early works. I'm also eager to go back to rehearsals,” he says, referring to his next show, a live performance called A Little Bit All Over the Place, anticipated to open in Phnom Penh in early June.

Better than theatre school

From the beginning, Laub preferred working with non-professionals, dancers and people outside traditional theatrical training.

“They act better because they didn't go to theatre school,” he states. “Back then, theatre schools [in Europe] were disastrous. I could practically tell which one someone came from. I like using non-professionals; I like to contrast them with highly skilled performers.”

He traces this approach to the 1970s performance art movement. “In the seventies, theatre was bringing in new voices from other art forms: Robert Wilson from visual art, Pina Bausch from dance, Marina Abramovic from performance art, the Wooster Group using video. All that was post-modern theatre. Dancers sometimes used text better than actors did. This change came with deconstructed theatre – non-linear narrative structures.”

But Laub resists being lumped into movements, his approach straightforward.“I use minimalism in the sense of economy. Theatre spoke too much. I don't like anything ornamental. I want the essential – not brutal realism, but oscillating between extreme realism and extreme artificiality, avoiding everything in between.

“People sometimes think I'm a formalist and I'm not. Form is very important, and I like the attempt at controlling it, but in live arts the performers as individuals are just as important, and individuals can be unpredictable. I just want to have a good time. I want the performers and the audience to have a good time, whatever that means. I don't have any ridged theoretical or ideological kind of background” he insists.

“I don't want to come across as anti-intellectual because I'm not. What I'm trying to say is that strictly conceptual art can sometimes become sterile as it often lacks an unpredictable human or personal element. I enjoy when someone suddenly bursts out laughing or expresses discomfort during their snapping. What is sometimes most interesting in a portrait is what escapes us.”

Coming to Cambodia

Laub's relationship with Cambodia began in 2011, working extensively with Phare Ponleu Selpak in Battambang. When Covid shut down his European operations, he returned.“I came back because I knew I could work here with dancers and artists I love,” he says. “Most of my choices are aesthetic – not just visual, but behavioural. I'm drawn to Cambodia for aesthetic, non-exotic reasons.”

During lockdown in Brussels, he rediscovered the only remnants of Snapping in the form of a faded trailer which is now part of the show.“The first difference I noticed was speed – in the original, everyone was smoking, you could hear them coughing, they moved slower. Now people are faster. They don't smoke, they take selfies. Attention spans are shorter. Just doing a remake would be boring.”

“In Cambodia, what struck me was the range of dance – from Apsara to hip-hop. That range motivated Snap Dance.”

The current installation, co-produced with IFC and Phare Ponleu Selpak, presents what the press release calls “a gallery of Cambodian portraits” – people from various social and professional backgrounds, as well as dancers from classical ballet, ballroom dancing and K-Pop, all moving without music. Viewers hear only footsteps, breathing, the rustle of costumes and the snapping of fingers that gives the piece its name.

Laub is characteristically modest about the work.

“It's not that spectacular – it's more like portraits. Madison Now in Phnom Penh was spectacular, full of energy. [This installation] is minimal. But I like it.” Later he adds, “Let's not build expectations like you might for an intense stage performance. I'm not into hype and this is a simple piece, something with a little more distance. But yeah, I like it. Or I wouldn't show it.”

Looking back at fifty years, Laub acknowledges he wasn't consciously making portraits in 1981.

“I wasn't aware that I was making portraits. I only started officially doing portraits in 2011. But when I saw that video, I thought, wow, that really consists of a portrait with a rhythmical structure. So it's a sound piece as much as it is a portrait piece.”

Minimalism without ornament

When speaking of his aesthetic, he again comes back to his roots in performance art.

“I worked with Marina Abramovi? – one of the founders of body art and one of my closest friends. You'd go to galleries with nothing on the walls, bodies were used as canvas, and it was art. I came from that niche.”

But pure performance art, with its reliance on a single concept, didn't satisfy him.

“I thought, 'Why no music? Why no video?' Why no talking? And later on, Why no dancing? Performance art relied on one concept pushed to the extreme, and luck – no rehearsal. I'm a control freak. I needed structure.”

Once he began combining elements – dance, video, text, music – he faced questions of dramaturgy. His solution was to approach each medium from “an essential, non-ornamental approach”.

He cites Samuel Beckett as an influence.

“I like Beckett writing in French because he stripped the language to its core. That's what I mean by minimalism – economical, not academic.”

The resulting work has an almost meditative quality. There's something strangely satisfying about watching and listening to both pieces – the rhythmic snapping, the changing video display, all creating an unintentional ASMR effect that draws viewers intimately into the exhibit.

Documentation and ethics

Laub's work often incorporates real stories from real people. During his Portrait Series: Battambang project, something unexpected occurred.

“The ethical position becomes interesting when someone shows up unexpectedly with a story – like the man who walked kilometres to talk about his genocidal past. I wasn't looking for that. For instance, in [the piece], there's a scene where five women are crying because they were abused.”

Laub explains how this scene came about.

“A woman came in, started crying in a language I didn't understand. We didn't even have a good translator; all the good ones were in Phnom Penh at the Khmer Rouge trials. The first time, I just felt empathy. Then another woman came in, crying again. Until there were five. I put them together. We orchestrated that into a cacophonic scene. They worked on it together.”

“They kept coming back – 'I can cry better than that.' It was unbelievable.”

He hadn't sought this out or planned for it. He wasn't looking for psychological breakthroughs or collective healing. But watching these women work together, return voluntarily, take ownership of their own testimony – something happened that he hadn't anticipated.

“I didn't mean for it to be therapeutic,” he says, careful about the distinction. What he rejects is the artist-as-healer posture. “I dislike artists who claim to educate or heal. I get as much out of it as they do. I'm not pedagogical. I'm the opposite of a messianic artist. I am not a guru-like figure.”

But that doesn't mean he didn't recognise what was happening. The process became cathartic for the women – organically, instinctually, without him engineering it. His role was different: give them complete control, the ethical safeguard being involvement.

“When I work on portrait, I involve the subjects in the creative process. They can take out anything they dislike, even withdraw the entire piece. That way I don't live with guilt of exploiting or hurting anyone, at least consciously. I show them the final result before it goes public. They have absolute veto rights.”

Three spaces, no fixed view

At IFC, the installation will move through three spaces – the exhibition gallery, the bistro and the cinema. As viewers enter the gallery, they'll encounter the original 1981 trailer for Snapping playing on a small television. On both side walls, visible simultaneously, Snapping 2025 is projected – each side featuring twelve individuals of all ages and backgrounds, twenty-four in total.

Moving from the gallery through the bistro space, viewers will find a large screen showing full body images of dancers, one at a time, dancing and snapping. This functions as an introduction, a segway, to Snap Dance, the second component of the overall installation. Then in the cinema, the full Snap Dance will be projected on stage in a loop with solos in between.

Laub speaks about seeing Abramovic's show in Manchester, where simultaneous stages saw 800 people moving around, becoming part of the performance.

“My relationship to the audience is one of respect. Even in the seventies, I never meant to provoke anyone but myself. My goal is to entertain myself and others,” he says. “At the French Institute, I want flexibility. Viewers can sit, walk, stay two minutes or twenty. It's more environmental; the audience becomes part of it.”

This is the punk sensibility in practice. It's clear throughout our conversation that Laub is wary of pretension, of making his work sound more esoteric than it is.

Near the end of our chat, he returns to this concern: “I don't want to scare people off. Sometimes people think, 'this is really complicated stuff', which really it isn't. I noticed that in Battambang in 2011; I worked with people who couldn't read or write, who understood my work a hell of a lot better than people who went ten years to university.”

He still believes real understanding comes from instinct, not theory. From recognising something true without needing anyone to explain what you're supposed to think or feel. Next week at the French Institute – three rooms, no fixed position, stay two minutes or twenty. Nobody's going to tell you which is right.

Michael Laub may have been called many things over the past four decades – post-dramatic, post-modern, minimalist, pioneer – but at his core, he remains what he was in 1981: a punk rocker who thought theatre was dead and keeps making it anyway.

Portrait Series – Snapping 2025 / Snap Dance will open at IFC in Phnom Penh with a reception on Wednesday, November 12 at 6pm, running through Saturday, November 15.

Wiebke Hüster, Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung (F.A.S.), 9 November, 2025

Portrait of the Choreographer Michael Laub: A Lonely Dance in a Hotel Room

The choreographer and director Michael Laub presents his new video installation “Snapping 2025 / Snap Dance” in Cambodia — a portrait of a rebel who has devoted his life to the fleeting nature of live arts.

In the 1970s, young performance artists didn’t show their work in theaters but in museums and galleries. “Maniac Productions” was the collective founded by Michael Laub and Edmondo Za that helped define the early days of video art in Sweden. At the Fylkingen Center for Intermedia in Stockholm, they found one of the rare art venues that had video equipment.

Sweden, 1975. Among young Central Europeans, the country was seen as the embodiment of sexual freedom. Alcohol was rationed, and when people drank, they drank seriously. Michael Laub had just arrived from Belgium at the age of 21. His first video work, “Infection,” shows two very young faces — Laub himself and Marinka Kordis. Over the image, Laub’s off-screen voice sings on a six-minute loop with minimal variation: “She got tired of me, tired of me, tired, tired, tired, she got tired of me.” She simply doesn’t want him anymore. What is left to say? There’s something touching about the way they sit there. The singing feels meditative, awkward. How can someone at 21 already have such artistic distance from his own heartbreak?

Art was more manic in its self-image

At the same time, one witnesses a kind of healing — a farewell ritual. It is both the end of a love story and, symbolically, the end of Western European theater history. The drama is over before the artwork begins. There are no tears, no accusations, no shouting. The effect is similar to Woody Allen’s 1970s films, where talking about relationships — and problems — became the art form of the time. You want to laugh and yet you’re moved. Laub’s humor is as sardonic and playful as Allen’s, but his work is the opposite of wordy.

“Infection” was Laub’s first work and one of the first videos produced by Maniac Productions, which also created live performances. Like the film, they dealt with obsession, and their method was obsessive repetition. The influence of minimalist composers such as La Monte Young, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass was significant. Laub thought: “Minimalism as a concept could surely be applied to theater.”

He decided to pursue that idea, even though he already had issues with strictly conceptual art: “I always thought that art lacked a personal element. But Marina Abramovic and Ulay were among the few performance artists I found interesting — their work, like Vito Acconci’s, was very personal.” Abramovic and Ulay, slightly older than Laub, represented Body Art — the body as the

canvas. Abramovic became known for carving a star into her stomach and filming it. Maniac Productions, by contrast, was more manic in its self-conception, often perceived as self- destructive. Alongside minimalist music, Laub listened to another genre of the time: punk rock. From the beginning, he aimed to turn personal, existential experience into artistic material rather than translating abstract concepts.

In Amsterdam, where Abramovic and Ulay shared a communal house, one evening all the young artists flocked to a gallery where nothing hung on the walls. It was one of the first galleries for performance art. Almost nothing happened that night — just a guy hitting something with a hammer every few minutes. That was it.

The impulse for “Infection”, on the other hand, wasn’t theoretical. Laub had been left for the first time. His girlfriend told him she was tired of him — literally: “I got tired of you.” Back then, Laub’s energy was directed against society’s need for entertainment. That has changed: “Today I like being entertained. And I do everything I can to make my work entertaining.”

What people find entertaining is, of course, subjective. At fifteen, Laub saw his first Ingmar Bergman film and has since felt most entertained by Bergman’s bleakest works.

His years in Sweden shaped him with feelings of alienation and foreignness. It’s no wonder his favorite Bergman film was “The Silence” — people hardly spoke in Swedish society back then. Until the mid-1990s, Sweden co-produced many of Laub’s increasingly ambitious works: Kulturhuset Stockholm, Moderna Museet, and eventually Dansens Hus.

A filmmaker, a choreographer, a Fassbinder spirit

Looking back, Laub’s early performance — accompanied by his own recorded singing — was extraordinary. In none of his more than thirty productions did he appear again. Only in his film “The Post Confinement Travelogue” (2023) does he return in front of the camera — and even dances. We see him wandering through Phnom Penh at night, surrounded by traffic, then driving through the Cambodian countryside, pausing by rice fields to smoke a cigarette. In the fields, two dancers appear. We see what Laub’s autobiographical figure sees. He himself dances alone in a hotel room in Battambang. The film is both beautiful and sad. Always lean, his eternally tanned face now shows age; his long dreadlocks have turned gray.

One reason Laub appears on camera, though he dislikes doing so, is the absence of his dancers. During the pandemic, his international ensemble scattered across the globe. As a result, several unforgettable productions can no longer be staged. Laub became a painter without a canvas, a writer without paper. In long phone calls, he said that for the first time in his life, he wished he had devoted himself to another art — envying painters for being able to paint, and writers for being able to write.

Eventually, he decided to embark on a laborious task: documenting fifty years of work in a book. With Miriam Schmidtke and longtime producer Michael Stolhofer, he created a non-chronological catalog titled “Rewind Song.”

The art of vanishing

Since the end of the pandemic, curators and producers have urged him to form a new company. For now, however, his theater works must be considered lost — they exist only as video recordings and in our memories. His colorful, ironic, Bollywood-inspired dance piece “Total Masala Slammer / Heartbreak No. 5” (2001) — gone. His remarkable “H.C. Andersen Project – Tales and

Costumes” (2003), dedicated to the failed dancer and the dances in Andersen’s writings — gone. “Fassbinder, Faust and the Animists” (2017) and the exuberant film-history-inspired “Rolling” (2019)? Gone.

Merce Cunningham once said that dance gives you nothing back — no images to hang on the wall. It leaves behind only thoughts made physical, gestures that fade, vanished beauty, lost virtuosity.

How can a director so steeped in cinema not see the advantage of theater by comparison? Film ages — gestures, speech, acting styles, clothes, hairstyles, cars, everything. Laub’s dance theater, however, could be revived in the present with a new cast. Because this rebel and anti-conformist has created pieces that are, in truth, classics. Laub’s laconic reply: “Transience is part of live arts. I never had the illusion of building a repertoire. And it doesn’t help to resist changes in casting.”

The portrait as reinvention

Laub’s other great invention can’t really be reconstructed — only reinvented. It grew out of his perception of the limits of conceptual art. Transferring musical minimalism to theater was one step; the next was bringing the portrait from visual art into theater.

Around the world, Laub cast his performers by asking them to stand before a simple paper backdrop, like in a photo shoot, and say or do whatever they felt like. He then wove their stories and lives together into his “Portrait Series.”

Here, finally, was the personal, human element he had missed. In 2004, he even portrayed Marina Abramovic — the artist appeared herself.

Like Abramovic, Michael Laub is obsessed with death, love, beauty, intoxication, sex, the making of images — the ones others draw of us, and the ones we hold of ourselves — and with the fear that every artist knows: that the next work might fail, or not be understood. That’s why Laub loves rehearsing most of all.

His latest work, “Snapping 2025 / Snap Dance,” continues the Portrait Series and is being shown this weekend at the S’Art Urban Art Festival in Battambang, Cambodia, in the city’s oldest disused movie theater. From November 12 to 15, the French Institute of Cambodia will also present the piece.

Laub’s fascination with classical dance traditions from around the world merges here with his simultaneously empathetic and unsparing urge to help people express themselves.

Rin Ousa, Cambodianess, 11 November 2025

PHNOM PENH — Snap Dance, a four-day video installation opening November 12 at the Institut français du Cambodge, invites audiences to experience dance as a language of rhythm and emotion, entirely without sound.

The series features performers ranging from apsara dancers and classical ballet artists to hip-hop practitioners, capturing the grace, energy, and individuality of each movement.

Part of Digital November 2025, Snap Dance—also called Snapping 2025—is a multi-screen installation produced by Belgian artist Michael Laub in collaboration with the Cambodian NGO Phare Ponleu Selpak.

Guided solely by breath, rhythm, and feeling, the dancers create moments that are at once hypnotic, intimate, and powerful. On screen, viewers encounter a gallery of Cambodian portraits, each revealing the strength and fragility of human expression.

The collection highlights performers from diverse backgrounds, offering a window into their unique identities and personal stories.

Laub, a pioneer of post-dramatic theater, is celebrated for transforming everyday gestures and cinematic elements into compelling visual experiences that blend realism and fiction. Through Snap Dance, he revisits the minimalist origins of his 1981 installation Snapping, reimagining it through contemporary dance while continuing to explore the beauty, challenges, and vitality of real life.

In 2024, Laub collaborated closely with dancers from the Royal University of Fine Arts, the Secondary School of Fine Arts, and Phare Ponleu Selpak for his creation Madison Now.

This year, Digital November continues its mission to expand access to new technologies while showcasing the richness of digital arts—from immersive experiences to innovative audiovisual performances. Through this exhibition, the French Institute contributes to a global dialogue about how technology shapes our engagement with art, creation, and society.

Now in its ninth edition, Digital November has become an international celebration of digital culture, reaching more than 70 countries and 130 cities in 2024. The event unites creators, professionals, and audiences to explore innovative uses of technology and artistic expression.