Michael Laub / Remote Control Productions

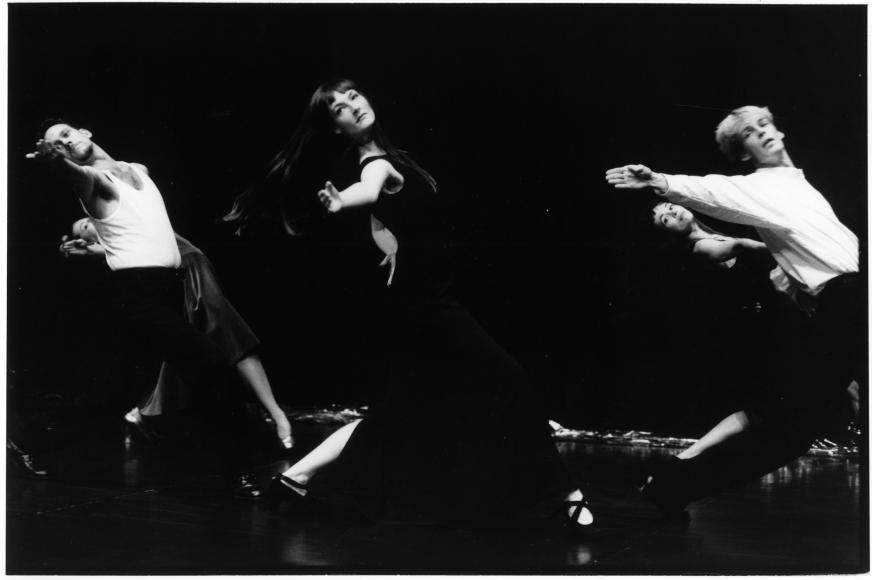

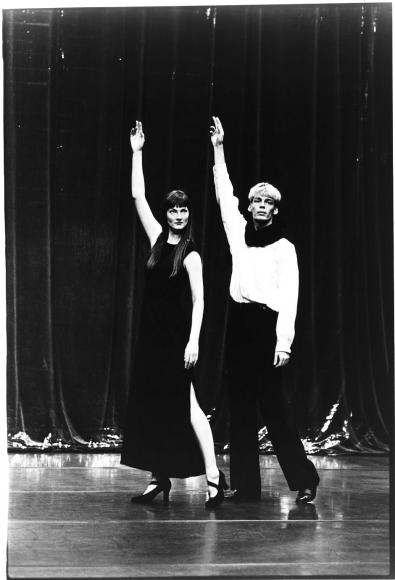

Daniel and the Dancers (1994)

PHOTOGRAPHY / VIDEO / CREDITS / PRESS

"So now you are working with tall thin athletic white people who say they don’t have any psychological problems so you say OK. And you tell yourself relax you’re gonna do a new piece an abstract pretty dance with no plot. But then the narrator has sudden violent mood-swings. So you get pissed off. I mean that’s not much for an introduction so you throw in a few love scenes. I know Dick’s hung up on one of these trashy music-hall artists from out of space, he wants to take her away from all this. I mean she’s got sleaze-bags staring at her tits all day maybe you should get into science-fiction, you’ve already done soap opera but then you’re stuck in planet without love and all you can think of is her Danish accent in French. I mean this is one of these cheap European co-production deals you have to take some of their dancers they have to take one of your singers you wanted another one too but couldn’t afford her so you just got the first one on tape again. You have to translate some of it into German too but that’s OK."

CREDITS

Directed by Michael Laub

Music Larry Steinbachek

Scenography Michael Laub

Lighting Kamal Ackarie and Michael Laub

Costume designer Niall Rea

Costume-maker Jaqueline Mayen

Sound Peter Jongelie

Technical Director Kamal Ackarie

Artistic Consultant Hans Tuerlings

Executive Producer Renata Petroni

Assistant Director Barbara Ehnes

Performers Richard C. Crane, Charlotte Engelkes, Kristin De Groot, Idit Herman, Eelco Roovers, Karl Schappell, Gabi Sund, Jan Zobel

Produced by Hans Tuerlings, Raz (Tilburg), Remote Control Productions

Co-produced by Theater am Turm (Frankfurt), Dansens Hus (Stockholm), [Nes]theaters (Amsterdam), Lantaren Venster (Rotterdam)

Supported by Northern Telecom Europe Limited, Theater Instituut Nederland, and Fond voor de Podiumkunsten

Subsidised by the Ministry of OCW, the Province of Brabant and the City of Tilburg.

PRESS

Irene Sieben, Berliner Morgenpost, 04.03.1996

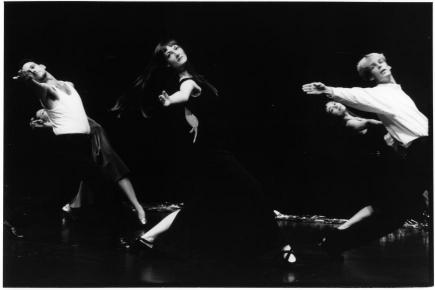

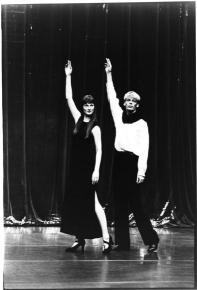

The carefully measured monologues and dialogues in English, German, and French seem to be desperate attempts to find a language between highly neurotic, inhibited and hysterical human beings from different starts. They’re verbal outbursts, much like orgasms. The minimalist step-patterns appear to smooth the mean, harsh atmosphere of sexual insinuations. These patterns take place at the back of the stage, which gains in importance throughout the evening in creating density, space and emotional distortion – a type of habitual survival

training.

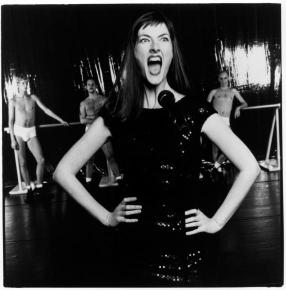

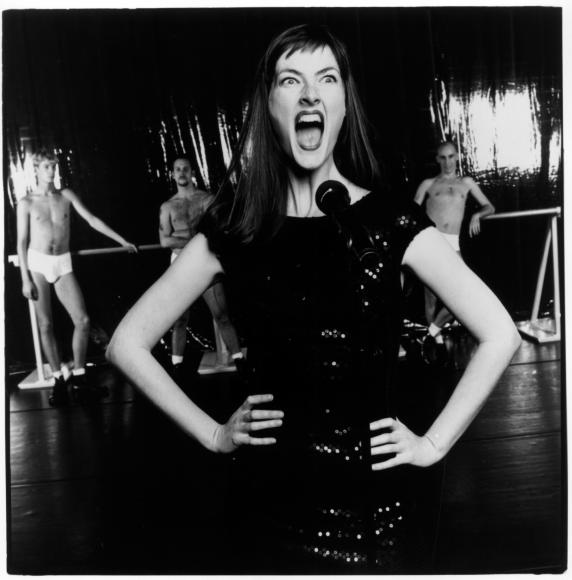

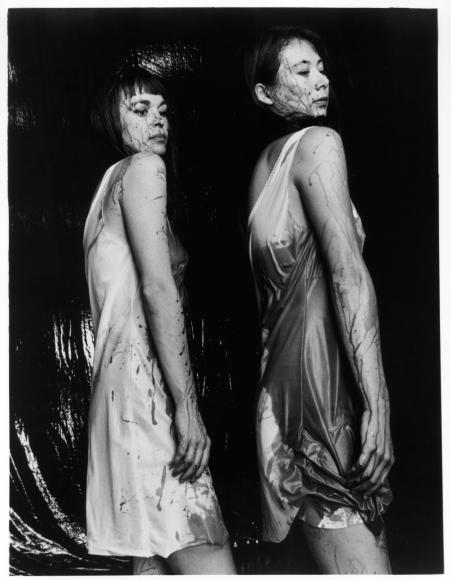

The cheering texts of the fantastic and deeply touching performer Charlotte Engelkes, change to loud shrieks when her companion on occasion forcefully hits her neck onto the microphone. (...) The piece is absolutely full of sadistic side-cuts. But the actors do suddenly cut back into a smile, into everyday life, into their role, into the dream layer, into the deepest distress of loneliness and abuse. The spectacle that seems to be about the search for material, turns out to be a splintering drama of the human psyche and unfulfilled basic instincts. Fiction and reality melt together in an alarming manner. The audience is left feeling always a bit too slow, too clumsy, too normal and too moralistic.

Gerald Siegmund, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 24.02.1996

Michael Laub’s theatre is an attempt to de-dramatize theatre with its own means. It is a theatre and dance piece about the components of a theatre and dance piece, an ironic Godard film on stage, a collage consisting of bits of splatter, horror and porno films, cinemascope music by Larry Steinbachek, cheap science-fiction and raw feelings. The fact that our lives are enacted more and more, while the real life takes its place on stage to the same extent between signs and quotations. (...) The theatre of Remote Control works with the unease of the actors on stage. Even the audience does not remain untouched by the powerful images at certain moments. Michael Laub proves to be a virtuous zapper, who knows how to create an appealing dish out of unappetizing, endless nonsense. He moves formally within an accepted field and proves to have control over the basics of anti-illusionistic theatre, of which he is one of the founding fathers.

Gerdie Snellers, de Volkskrant, 08.10.1994

...all is flavoured with a cold big-city atmosphere, with lack of communication, egocentricity and the inability to do things differently. Laub lets into the theatre life in all its rawness. (...) The social manners presented to us by him are in any case tragic and interspersed with an ominous amount of violence.

Monna Dithmer, Politiken, Kopenhagen, 09.03.1996

This is masterful comedy – served by the Laub diva Charlotte Engelkes – and a masterclass in the Laub technique, the aim of which is to smash the whole theatre process into bits and pieces and display them in all their naked glory.

Marten Spangberg, Dagens Nyheter, 07.02.1995

When Michael Laub and Remote Control Productions create their performances, the very absence of ethics is what makes the strongest impression on me. In Daniel and the Dancers (...) they don’t even play theatre. (...) The theatrical illusion has been destroyed, and what is happening on stage is simply another reality. (...) When Michael Laub directs, it’s impossible to decode the texts or find interpretations – such methods are no longer valid. The collision between ambivalence and extreme clarity, is the impossible task that Laub engages in.

Dirk Fuhrig, Frankfurter Rundschau, 24.02.1996

Michael Laub has created a wonderful and unusual rhythm for the entire performance. The many pictures change quickly, however not obviously. Quiet, almost sad moments of tension are interspersed amongst bright aggressive scenes. There are also occasional moments in which syrupy heartaches from global soap operas seem to transform into real melancholy. Or does Michael Laub merely overwhelm us with the subtle lust of sentimentality at such points?

Anna Angström, Svenska Dagbladet, 05.02.1995

The wall between dream-world and reality is as frail as the surface of a soap-bubble. Remote Control makes the holes visible; assisted by the music, the group zaps between scenes, seemingly at random, but with perfect timing and irony. The glitches between ‘on’ and ‘off’ are sort of mental choreography in a manipulated contemporary world where nobody cares to listen, no matter how loudly you scream about blood and damaged communications.

Notes by Robert Steijn, December 1994

(...) He zaps on his players and he zaps them off again. Over the heads of the audience, he signals when the players are to come on during the performance, when they are to tone down their lines, and even when a scene s to end. Because he is also in direct contact with the sound engineer, he determines when the music starts and when it stops. The timing varies from night to night. It depends on the director’s mood, but also on his assessment, every single evening, of how the audience reacts to a certain scene. In this way, Laub tentatively explores how long a scene remains viable in the spectator’s imagination. If he suspects that the maximum has been reached, the music stops inexorably, or some other players come on, taking over the scene. Thus, Laub re-shuffles the way the scenes are composed into sequence – even if the order of the scenes never changes. It is the moments in-between, the splices, that vary in duration from performance to performance. The rhythm of the performance also varies nightly. Sometimes these splices are felt to be extremely brief and the performance becomes a hectic succession of a variety of impulses. Sometimes they expand into a more protracted silence, while the structure becomes more open, the atmosphere more relaxed. Ultimately, the director is always the one to determine the performance’s atmosphere. This responsibility does not lie with the actors. Relieved of this burden, they are able to exhibit themselves with unparalleled casualness. In all their actions, they seem to remain more or less themselves, irrespective of the reactions of the audience. Their performance attains a cool beauty, intimate, yet nevertheless aloof in an illusive way. This is due to the fact that their acting arises from an intimacy, created together with the director during rehearsals. While, at the same time feeling no need whatsoever to seek contact with the audience for their timing. (...) This truncation of scenes tends to create silences in which for a while nothing is seen or heard. One situation has then been punctured, the next one still has to start. These brief intervals show that every scene stands on its own, and that it is certainly not a question of a progression in which a scene organically develops from the previous one. Each moment stands isolated, which means that, for the players, their roles can have no underlying structure as an aid to seeing the performance as a whole. Relevant is only a scene’s momentary effect, although whatever has continued to fester beneath the skin may occasionally come out in a resounding monologue, in an appealing one-liner or some unequivocal action. In this way, psychology remains on the outside, a surface phenomenon. However, this is not to say that no violent emotions are shown. Or that such emotions do not register as true to life. On the contrary, particularly the players from Laub’s regular group at times manage to render a lucid emotion.